Johan Deckmann

http://Deckmann.com

Johan Deckmann

http://Deckmann.com

by Dan Piepenbring / The Paris Review

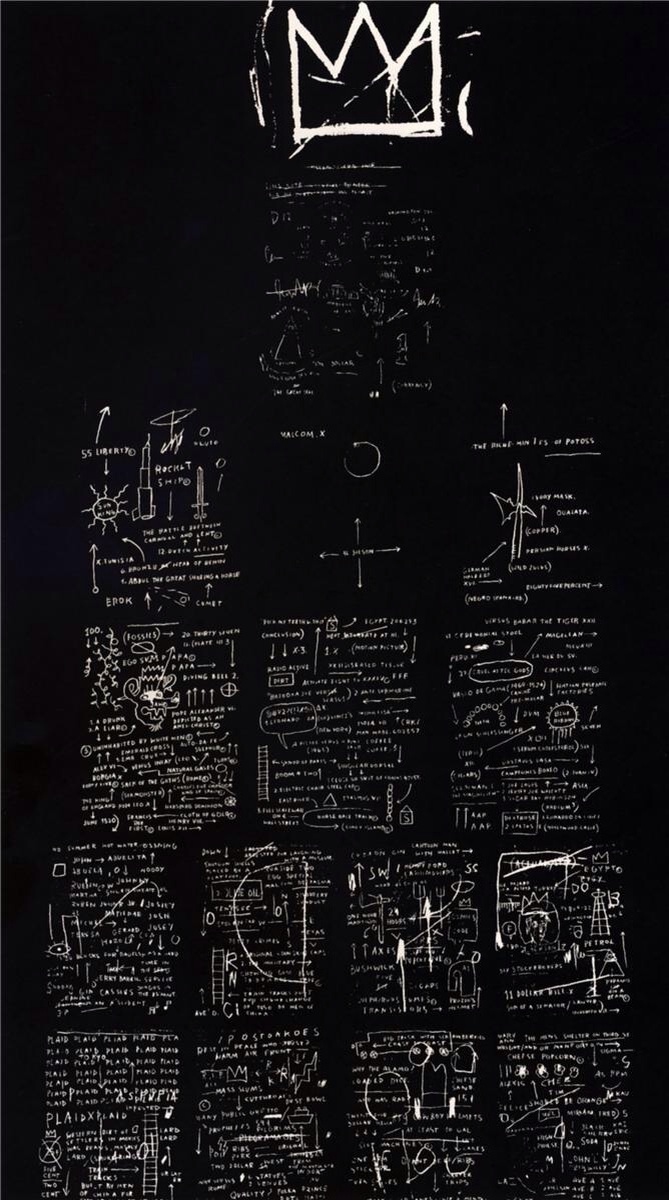

Aram Saroyan’s lighght

Jean-Michel Basquiat

Philip Davis pleasures his brain with shifting Shakespearean syntax, measures the results on an electroencephalogram, and finds evidence that powerful writing can literally change the ways in which we think ...

From THE READER magazine

I have always been very interested in how literature affects us. But I don't really like it when people say, "This book changed my life!" Struggling with ourselves and our seemingly inextricable mixture of strengths and weaknesses, surely we know that change is much more difficult and much less instant than that. It does scant justice to the deep nature of a life to suppose that a book can simply "change" it. Literature is not a one-off remedy. And actually it is the reading of books itself, amongst other things, that has helped me appreciate that deep complex nature. Nonetheless, I do remain convinced that life without reading and the personal thinking it provokes would be a greatly diminished thing. So, with these varying considerations, I know I need to think harder about what literature does.

And here's another thing. In the last few years I have become interested not only in the contents of the thoughts I read--their meaning for me, their mental and emotional effect--but also in the very shapes these thoughts take; a shape inseparable, I feel, from that content.

Moreover, I had a specific intuition--about Shakespeare: that the very shapes of Shakespeare's lines and sentences somehow had a dramatic effect at deep levels in my mind. For example, Macbeth at the end of his tether:

And that which should accompany old age,

As honour, love, obedience, troops of friends,

I must not look to have, but in their stead

Curses, not loud but deep, mouth-honour, breath

Which the poor heart would fain deny and dare not.

I'll say no more than this: it simply would not be the same, would it, if Shakespeare had written it out more straightforwardly: I must not look to have the honour, love, obedience, troops of friends which should accompany old age. Nor would it be the same if he had not suddenly coined that disgusted phrase "mouth-honour" (now a cliché as "lip-service").

I took this hypothesis--about grammatical or linear shapes and their mapping onto shapes inside the brain--to a scientist, Professor Neil Roberts who heads MARIARC (the Magnetic Resonance and Image Analysis Research Centre) at the University of Liverpool. In particular I mentioned to him the linguistic phenomenon in Shakespeare which is known as "functional shift" or "word class conversion". It refers to the way that Shakespeare will often use one part of speech--a noun or an adjective, say--to serve as another, often a verb, shifting its grammatical nature with minimal alteration to its shape. Thus in "Lear" for example, Edgar comparing himself to the king: "He childed as I fathered" (nouns shifted to verbs); in "Troilus and Cressida", "Kingdomed Achilles in commotion rages" (noun converted to adjective); "Othello", "To lip a wanton in a secure couch/And to suppose her chaste!"' (noun "lip" to verb; adjective "wanton" to noun).

The effect is often electric I think, like a lightning-flash in the mind: for this is an economically compressed form of speech, as from an age when the language was at its most dynamically fluid and formatively mobile; an age in which a word could move quickly from one sense to another, in keeping with Shakespeare's lightning-fast capacity for forging metaphor. It was a small example of sudden change of shape, of concomitant effect upon the brain. Could we make an experiment out of it?

We decided to try to see what happens inside us when the brain comes upon sentences like "The dancers foot it with grace", or "We waited for disclose of news", or "Strong wines thick my thoughts", or "I could out-tongue your griefs" or "Fall down and knee/The way into his mercy". For research suggests that there is one specific part of the brain that processes nouns and another part that processes verbs: but what happens when for a micro-second there is a serious hesitation between whether, in context, this is noun or verb?

The main cognitive research done so far on the confusion of verbs and nouns has been to do with mistakes made by those who are brain-damaged and thus on the possible neural correlates of grammatical errors and semantic violations. Hardly anybody appears to have investigated the neural processing of a --˜positive error' such as functional shift in normal healthy organisms. This truly would be a small instance of inner drama.

We decided to experiment using three pieces of kit. First, EEG (electroencephalogram) tests, with electrodes placed on different parts of the scalp to measure brain-events taking place in time; then MEG (magnetoencephalograhy), a helmet-like brain-scanner which measures effects in terms of location in the brain as well as their timing; and finally fMRI (Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging), those tunnel-like brain-scanners which focus even more specifically on brain-activation by location. I knew nothing much of this: I am indebted to Professor Roberts and to Dr Guillaume Thierry of Bangor University who joined us in the enterprise.

With the help of my colleague in English language Victorina Gonzalez-Diaz, as well as the scientists, I designed a set of stimuli--40 examples of Shakespeare's functional shift. At this very early and rather primitive stage, we could not give our student-subjects undiluted lines of Shakespeare because too much in the brain would light up in too many places: that is one of the definitions of what Shakespeare-language does. So, the stimuli we created were simply to do with the noun-to-verb or verb-to-noun shift-words themselves, with more ordinary language around them. It is not Shakespeare taken neat; it is just based on Shakespeare, with water.

But around each of those sentences of functional shift we also provided three counter-examples which were shown on screen to the experiment's subjects in random order: all they had to do was press a button saying whether the sentence roughly made sense or not. Thus, below, A ("accompany") is a sentence which is conventionally grammatical, makes simple sense, and acts as a control; B ("charcoal") is grammatically odd, like a functional shift, but it makes no semantic sense in context; C ("incubate") is grammatically correct but still semantically does not make sense; D ("companion") is a Shakespearian functional shift from noun to verb, and is grammatically odd but does make sense:

A) I was not supposed to go there alone: you said you would accompany me.

B) I was not supposed to go there alone: you said you would charcoal me.

C) I was not supposed to go there alone: you said you would incubate me.

D) I was not supposed to go there alone: you said you would companion me.

What happened to our subjects' brains when they read the critical words on screen in front of them?

So far we have just carried out the EEG stage of experimentation under Dr Thierry at Bangor. EEG works as follows in its graph-like measurements. When the brain senses a semantic violation, it automatically registers what is called an N400 effect, a negative wave modulation 400 milliseconds after the onset of the critical word that disrupts the meaning of a sentence. The N400 amplitude is small when little semantic integration effort is needed (e.g., to integrate the word "eat" in the sentence, "The pizza was too hot to eat"), and large when the critical word is unexpected and therefore difficult to integrate (e.g., "The pizza was too hot to sing").

But when the brain senses a syntactic violation there is a P600 effect, a parietal modulation peaking approximately 600 milliseconds after the onset of the word that upsets syntactic integrity. Thus, when a word violates the grammatical structure of a sentence (e.g., "The pizza was too hot to mouth"), a positive going wave is systematically observed.

Preliminary results suggest this:

(A) With the simple control sentence ("You said you would accompany me"), NO N400 or P600 effect because it is correct both semantically and syntactically.

(B) With "You said you would charcoal me", BOTH N400 and P600 highs, because it violates both grammar and meaning.

(C) With "You said you would incubate me", NO P600 (it makes grammatical sense) but HIGH N400 (it does not make semantic sense).

(D) With the Shakespearian "You said you would companion me", HIGH P600 (because it feels like a grammatical anomaly) but NO N400 (the brain will tolerate it, almost straightaway, as making sense despite the grammatical difficulty). This is in marked contrast with B above.

So what? First, it was as Guillaume Thierry had predicted. It meant that "functional shift" was a robust phenomenon: that is to say, it had a distinct and unique effect on the brain. Instinctively Shakespeare was right to use it as one of his dramatic tools. Second the P600 surge means the brain was thus primed to look out for more difficulty, to work at a higher level, whilst still accepting that fundamental sense was being made.

In other words, while the Shakespearian functional shift was semantically integrated with ease, it triggered a syntactic re-evaluation process likely to raise attention and give more weight to the sentence as a whole. Shakespeare is stretching us; he is opening up the possibility of further peaks, new potential pathways or developments. Our findings show how Shakespeare created dramatic effects by implicitly taking advantage of the relative independence--at the neural level--of semantics and syntax in sentence comprehension. It is as though he is a pianist using one hand to keep the background melody going, whilst simultaneously the other pushes towards ever more complex variations and syncopations.

This is a small beginning. But it has some importance in the development of inter-disciplinary studies--the co-operation of arts and sciences in the study of the mind, the brain, and the neural inner processing of language felt as an experience of excitement, never fully explained or exhausted by subsequent explanation or conceptualization. It is that neural excitement that gets to me: those peaks of sudden pre-conscious understanding coming into consciousness itself; those possibilities of shaking ourselves up at deep, momentary levels of being.

This, then, is a chance to map something of what Shakespeare does to mind at the level of brain, to catch the flash of lightning that makes for thinking. For my guess, more broadly, remains this: that Shakespeare's syntax, its shifts and movements, can lock into the existing pathways of the brain and actually move and change them--away from old and aging mental habits and easy long-established sequences. It could be that Shakespeare's use of language gets so far into our brains that he shifts and new-creates pathways--not unlike the establishment of new biological networks using novel combinations of existing elements (genes/proteins in biology: units of phonology, semantics, syntax , and morphology in language). Then indeed we might be able to see something of the ways literature can cause affect or create change, without resorting to being assertively gushy.

I do not think this is reductive. Cognitive science is often to do with the discovery of the precise localization of functions. But suppose that instead we can show the following by neuro-imaging: that for all the localization of noun-processing in one place and the localization of verb-processing in another, when the brain is asked to work at more complex meanings, the localization gives way to the movement between the two static locations.

Then the brain is working at a higher level of evolution, at an emergent consciousness paradoxically undetermined by the structures it still works from. And then we might be re-discovering at a demonstrable neural level the experience not merely of specialist "art" but of thinking itself going on not in static terms but in dynamic ones. At present there is of course no brain imaging system that allows the study of continuous thought. But the hope is that, within experimental limitations, we might be able to gain a glimpse within ourselves of a changing neurological configuration of the brain, like the shape of the syntax just ahead of the realization of the semantics.

In that case Shakespeare's art would be no more and no less than the supreme example of a mobile, creative and adaptive human capacity, in deep relation between brain and language. It makes new combinations, creates new networks, with changed circuitry and added levels, layers and overlaps. And all the time it works like the cry of "action" on a film-set, by sudden peaks of activity and excitement dramatically breaking through into consciousness. It makes for what William James said of mind in his "Principles of Psychology", "a theatre of simultaneous possibilities". This could be a new beginning to thinking about reading and mental changes.

(Philip Davis is editor of The Reader magazine, and teaches in the School of English at the University of Liverpool. This article first appeared in The Reader, Number 23, pp. 39-43, and was prepared in collaboration with Neil Roberts, Victorina Gonzalez-Diaz, and Guillaume Thierry.)

1.

In societies dominated by modern conditions of production, life is presented as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has receded into a representation.

2

The images detached from every aspect of life merge into a common stream in which the unity of that life can no longer be recovered. Fragmented views of reality regroup themselves into a new unity as a separate pseudoworld that can only be looked at. The specialization of images of the world evolves into a world of autonomized images where even the deceivers are deceived. The spectacle is a concrete inversion of life, an autonomous movement of the nonliving.

3

The spectacle presents itself simultaneously as society itself, as a part of society, and as a means of unification. As a part of society, it is ostensibly the focal point of all vision and all consciousness. But due to the very fact that this sector is separate, it is in reality the domain of delusion and false consciousness: the unification it achieves is nothing but an official language of universal separation.

4

The spectacle is not a collection of images; it is a social relation between people that is mediated by images.

Guy Debord

http://www.bopsecrets.org/SI/debord/1.htm

Psychogeography for Beginners

by Magda Knight

Ever felt drawn to strange old warehouses or puzzled over why everyone looks like a robot on their way to work? With the aid of a few helpful exercises Mookychick shows you the semi-occult art of psychogeography - finding out how the environment you live in shapes the way you think. Becoming a psychogeographer is as easy as studying graffiti and poking your nose where it doesn’t belong…

Okay. Ever felt drawn to abandoned buildings and old warehouses? Ever had a favourite spot in a park? Ever noticed how people look like robots on their way to work? Ever moved into a new house and wondered who’s lived there before and if they were happy there? Ever felt uncomfortable in the city district with its huge skyscrapers? Ever felt like you’re in a science fiction film when you take the subway?

The chances are you’re already a psychogeographer. Guy Debord described psychogeography as ‘The study of specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organised or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals” in the first issue of Situationniste Internationale (1958).

He was talking about the way humans shape their environment, but also how the environment shapes humans.

About how you can pick up vibes from a place you’ve never been to before, and feel it’s a good or a bad place. This could be to do with the structure of a building, from a dark history of the area you’ve intuited… all sorts of things.

Psychogeographical techniques - The ‘Derive’ (‘drifting’ in French)

The best way to do a bit of psychogeography is just to mosey around with no pre-planned expectations. This is called going on a derive, or urban drifting. Let yourself be delighted by something new! Get to know a place in a different way than you did before, and remember that difference.

So if you go on a derive - that is, a gentle walk with the aim to discover something new about your area - try to find patterns where there aren’t any. look out for graffiti, words on shop-signs and posters. Talk to local people, and take plenty of photos.

Why take up an interest in psychogeography? Well, there are lots of reasons. You can do it on your own, you don’t have to join a group. You can’t be wrong - the worst that might happen is you might change your mind. And it’s important - how you behave every day shapes you. If you switch off and become a robot on your way to work or school like everyone else seems to, you’re wasting your day. Why not take a deep look around you instead?

When you apply psychogeographic techniques to explore your environment, you’re looking around you with open eyes. You’re seeing layers of information in otherwise dullsville surroundings. You’re making up stories for yourself, and you’re thinking. And you’ve acquired a new sexy-hot title - Psychogeographer!

Psychogeographic Derive - Exercise 1 - The Graffiti Derive

Set aside an afternoon and go somewhere safe and consumerist, like the hippest part of town wherever you live. But remember, you’re not there to do shopping. You can do exercises like this alone or with an interested friend. But with two of you the desire for shopping will automatically increase - so no shopping until the derive is over!

Your task for this adventure is to set yourself a time limit then spend the next couple of hours wandering around, noting down any graffiti you find, both by writing it in a notepad and taking photographs of it. This means that you’re not looking where consumerist society wants you to look - you know, at shops or billboards, the usual suspects. Screw that. Find yourself exploring bus stops, public toilets and sidestreets. Go to the places that are invisible when you’re purely focused on shopping. Notice all the things you’re not meant to see as a good little citizen - the cctv cameras, the drunks, the strange little hang-outs and alleyways.

When you’ve finished, treat yourself by going and buying something tiny and pointless and pretty, or even the pair of shoes you’ve had your eye on for so long, or buying a drink and sitting down outside in a cafe or little park, and really enjoy your consumerist moment - you’ve poked into the inner workings of the invisible city, so you’ve earned your Coke! Collect all your photographs and stick them in a scrapbook labelled Soho / Times Square / Blah / whatever your hip shopping district is called. You’ll be surprised at how much satisfaction and meaning you getting from collecting such unglamorous photos.

Psychogeography has many different branches and factions, many of whom fight with each other. In-fighting among psychogeographic groups is just playground tactics. It really doesn’t matter because they’re all on the right track and just approaching things from different angles. Yes, the geography of a landscape shapes the way people think - and it does this in a host of different ways that it’s up to you to find.

There are occult ways of looking at your surroundings. For example, you may have heard of ley lines - invisible lines of power that some people say dissect the earth. You can look into dowsing to find ley lines in your area and see if they affect it in any way - does a road lie directly on a ley line? Are there many buildings of importance all in a line where you live? If so, there could be a scientific explanation, or there could be a ley line. Or buildings might be designed with symbolism - squares suggest power and groundedness, circles represent eternity and calmness, triangles represent energy and stimulation… you’d be surprised how often shapes appear in architecture for a symbolic reason. For example, there is a Chinese bank in the financial district of London that has triangular points coming out of it in all directions - and the bank admits these were intended as ‘poison arrows’ to negatively affect the feng shui of rival banks in the area and get them to have worse business. Hey, if even super-straight banks are into psychogeography, then it can’t be that nutsy!

There are also social ways of looking at the world around you. If you live in a city, that’s a huge amount of people in one place - and obviously anyone in power is going to want to control those people rather than have them riot. So a city has a mass of different ways to get everyone to do stuff safely, without hurting each other, at the same time… think of walkways, traffic lights… so many signs to tell you how to behave and what to do that half the time you don’t even notice them. Looking out for these signs is a completely different way of looking at how a city is designed compared to occult studies of symbolism, but both of them are fascinating.

And you can discover this stuff for yourself - and you don’t need a huge amount of research to start doing it.

Psychogeographic Derive - Exercise 2 - The Freedom to Sit Derive

Again, go to the hippest part of town. This exercise is partly to answer the question - does a materialist society actually want you to sit down? After all, if you sit down, you’re not buying anything. But if you have been a bit of a shopaholic, then sitting down will give you the energy to get up again and go buy some more! Again, there’s no right or wrong answer, especially because all towns are different - it’s up to you to find out more.

Set aside an hour to find places in the hippest / busiest part of town where you could sit and enjoy the scene without buying or doing anything, if you wanted to. Look out for walls at a comfortable height, public benches, little public gardens, cafe areas. Whatever you can find.

If you see a perfect spot in a busy place that appears to be empty with no-one taking advantage of it, sit down in it and look around. Why do you think none of the passers-by have taken advantage of your amazing spot? Is it that your so-called ‘amazing’ spot actually smells of wee and you hadn’t noticed it before, or is it something else? How do people seem to treat you now you’ve sat down in this perfect public sitting space? Any different? Do they notice you more than they would if you were just walking around like they are?

If you find some spots where people ARE sitting down - public benches, little gardens, walls, bus stops, parks - take a look at them. What kind of people are they? Poor? Rich? What are their expressions? Are they sitting down for a purpose (exhaustion, waiting for a bus) or for fun? How are they behaving compared with people walking around? Jot down any thoughts you have about the people using these public sitting places in your notebook.

Whenever you go on a derive, always take a notebook. You’ll end up having surprising thoughts, going off on a tangent - and forgetting them immediately. Any notes you get - descriptions of people, ideas about how your city is used, amazing graffiti you found - all these thoughts are your own, not taught you by anyone. So they’re precious. Whether they’re for song lyrics, an art project or just a bit of a self-journey - an internal derive - you’ll be glad you had them one day.

Find out more about psychogeography

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Psychogeography (psychogeography on Wikipedia)

Conflux (one of the best psychogeography sites ever. Start here!)

Manchester Area Psychogeographic (some good articles and interviews)

Empty Streets (hardcore yet fun artsy psychogeography)

http://emptystreets.net/?cat=21

Flaneur (pretty but old site dedicated to urban life and the art of strolling)

More about flaneur (the art of walking around checking stuff out)

http://www.thelemming.com/lemming/dissertation-web/home/flaneur.html

Bop Secrets (nasty-looking but pretty interesting situationist / psychogeographical research site)

Unfinished Buildings (a small site dedicated to unfinished buildings)

Via http://www.mookychick.co.uk/

http://wombgallery.com

Story and photo by Rachel Ingram

Published in North Lake Travis Log (Features / Top Stories), June 22, 2011

Link: http://northlaketravislog.com/2011/06/22/jonestown-seniors-photographed-for-global-art-project/

Thanks to Kim Conley, Jonestown has made its mark on the global art scene by participating in a worldwide project called Inside Out. The project was founded by French artist JR after he won this year’s TED Prize — $100,000 and one wish to change the world. Using art for positive change, JR asked people across the world to transform personal identities into art by taking large-scale, black-and-white portrait photos and displaying them in public.

So far more than 4,000 people have participated, but Conley’s 27-photo exhibit could be one of the largest.

Inside Out has a few guidelines. Photos must be close-up portraits and in black and white. They also must be blown up to poster-size and displayed “in the wild” — in other words, out in the community.

Conley, who has been a photographer for 15 years and was published three times in a Chicago-based travel magazine, set a launch date of June 11 for her photo collection. She began taking photos in mid-April.

After working at the local Meals on Wheels and More program for two years, the choice was simple when deciding on a subject: North Shore seniors. She also came up with a name for the exhibit: Living History.

“That’s what seniors are,” Conley said. “They’re walking, talking, breathing history.”

The 27 photographed seniors are all Meals on Wheels participants who come to the Northwest Rural Community Center for lunch and socializing each day between 9 a.m. and 2 p.m.

“I’d like to make them feel like superstars for a minute because I think so many of them have lived really interesting lives and have great stories,” Conley said. “It’s a show of appreciation to them and what they bring to the community.”

One of the seniors went to a concentration camp as a child, and several of them have military and war stories. Some seniors spent their whole lives in Jonestown and have interesting stories of the city’s history and how it has changed in the last 50-70 years.

“Some people just know a lot,” Conley said. “Even if they haven’t gone through much, they have gathered so much information.”

Once Conley had all the photos she wanted, she submitted them to Inside Out to be displayed on the website, www.insideoutproject.net. In a month, Inside Out made the photographs into posters and sent them to Conley.

After getting the support of Jonestown Mayor Deane Armstrong and speaking at a City Council meeting, Conley got approval to display the 3-foot by 4-foot posters on the outside windows of the community center at 18649 FM 1431. As the saying goes, eyes are the windows to our souls, and Conley hopes looking into the eyes of the subjects in their close-up portraits will inspire residents to want to know more about the knowledge and experience local seniors have.

Twenty photos are on the front of the building and seven are on the side of the building. City Secretary Linda Hambrick suggested to Conley that she include senior North Shore musicians in her project. The musicians make up the seven seniors on the side of the building facing True Grits.

Some seniors enjoyed having their picture taken, while others had to be coaxed a bit. Whether they were camera shy or not, no one has told Conley they wished their photo wasn’t on display.

“I think some of them are a little intimidated by their own picture as they walk in every day,” Conley said. “But I think that’s good for you. It helps you accept yourself more. It helps you maybe realize you’re worth more than you thought. Then when you have people walking up to you saying your picture looks great, how can that do anything but help you with your self esteem?”

Inside Out participants were required to submit biographies with their photos, and in the next few months Conley will be compiling her subjects’ stories and photos in a book. She is hoping the book will be ready in three months and will be available at the community center and a couple local businesses.

Conley’s “Living History” project had its launch party June 11 with live music by some of the musicians photographed for the project. The next step in Conley’s participation with Inside Out is to upload photos of her work being displayed in public, so the whole world will see the Jonestown community center and its walls of “living history.”